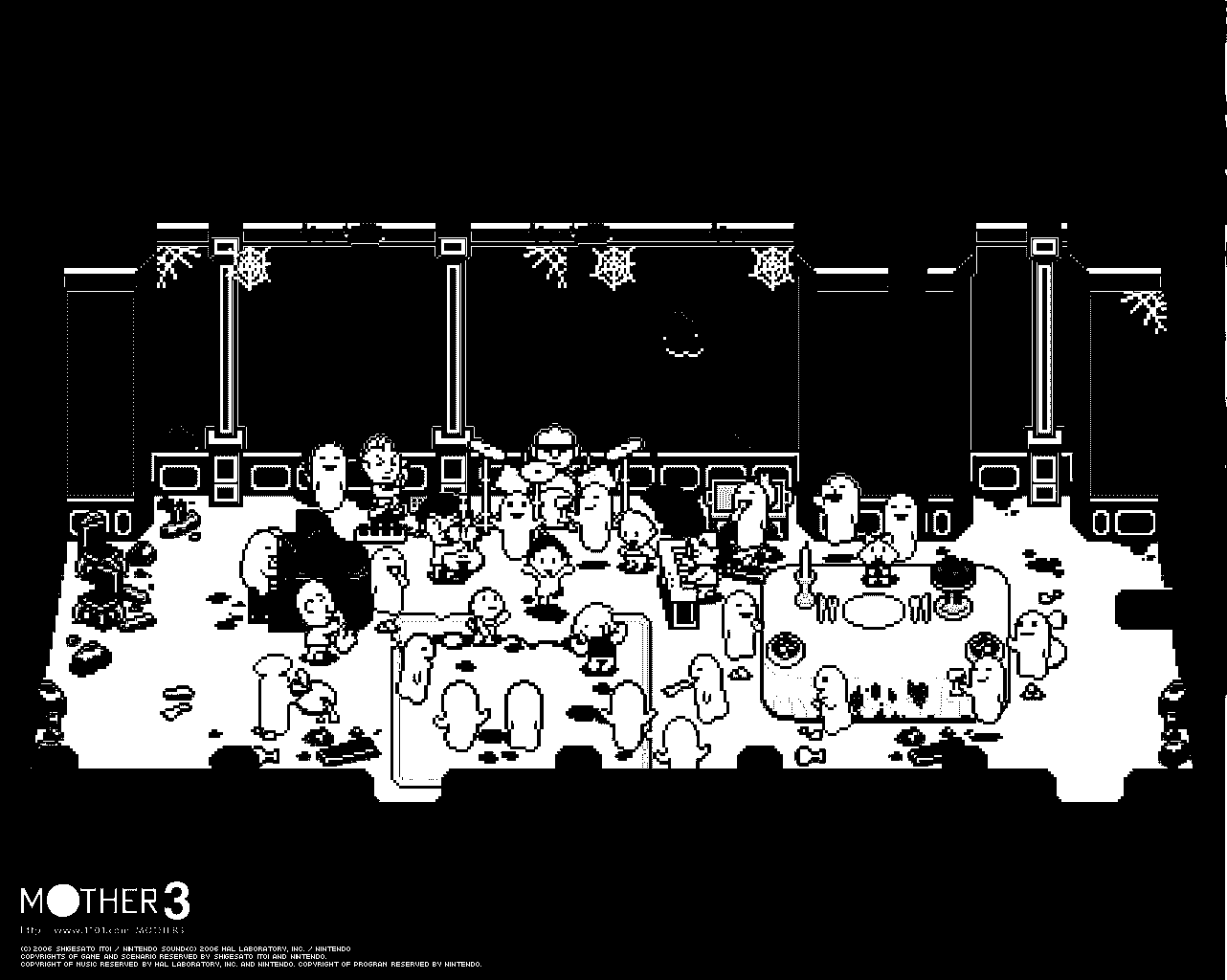

a review of mother 3

a review of mother 3

a videogame developed by brownie brown

and published by nintendo

for the nintendo gameboy advance

written by shigesato itoi

text by tim rogers

It’s impossible to lose in Mother 3.

And I don’t mean that in some kind of back-of-the-box quote fashion. I don’t mean “It’s a game so good it’s never over!” I mean, seriously, the only way to lose the game is to quit playing it. To take it out of your Gameboy Advance or Gameboy Advance SP or Gameboy Micro or Gameboy Advance SP with actual backlight or Gamecube Gameboy Player or Nintendo DS or Nintendo DS Lite and file it away in a drawer somewhere, and never play it again. Or, hey, even if you stop playing it for a week, or longer than a week, it can be said that you lost, for a short time. You can start winning again as soon as you start playing again.

How many players back in 1994 hadn’t raised each character in the four-character party up to level 99 before the epoch-making, soul-wrenching final battle in Mother 2? Probably not that many of them. I have owned and played and traded and even given away many, many copies of Mother 2, and nine out of ten copies had a save file at the last possible save point, minutes from the final boss, with four characters on level 95 or above.

That doesn’t happen in Mother 3 because Mother 3, as a videogame, is many fives of inches closer to perfection than Mother 2. In Mother 3, you can win battles with actual skill and reflexes. The battles are rhythm-based. Hit the attack button on-time to chain together hits. You can score up to sixteen hits in a sequence — a perfect number for combo hits in a game with a rhythm-based system, if you stop to think about it. The first hit is the strongest; each successive hint ranges from laughable to ineffective to moderate. Toward the middle of the game you might score 100 damage with the first hit, and then eight with the second hit. Keep hitting, though, and a 20 or a 25 might pop up here and there. It adds up in the end. Sticking with a combo to the sixteenth hit will see you scoring about triple the damage of a normal attack — that is, about the same amount of damage as three attacks, one from each party member.

Now, “a role-playing game with a rhythm-based battle system”. That alone isn’t enough to describe why, in videogame terms, Mother 3 is brilliant. It’s how the rhythm-based battle system is used that makes it brilliant. I feel compelled to make a list.

1. The battle music is excellent. How much of the cartridge space is reserved for music, I don’t know. A good guess would be “most of it”. Music is obviously very important to this game. It’s full of pounding drums, humming guitars, and chaotic synthesizers. The battle music is actually the least ambitious, composition-wise, of all the music in the game. Functionally, though, it’s excellent. There are so many battle themes, dozens of them, each with a different rhythm to master, each with different beats that register as “correct” for any given sequence.

2. The music messes with you. Sometimes the drums will fall out of a song. Sometimes the song will stop altogether. Sometimes enemies will use attacks that scatter the rhythm. And sometimes — sometimes — the songs are just in bizarre math-rock time signatures that no ear is born being able to respond to. Some parts of the songs have more prominent drumlines than other parts of the same song. This is brilliant because:

3. The game lets you choose when to start your attack. Like in any turn-based RPG — as in, say, Dragon Quest — you put in commands for each character in your fighting party, and then the characters act in turn based on their agility rankings. Just before a character’s attack turn in battle, a window pops up, saying it’s so-and-so’s turn to attack. There’s a little blinking arrow in the corner. Press the A button to begin the attack. So if the song is at a part where it’s hard to discern the rhythm, you can wait for the good part. If this sounds like it might be kind of frustrating, then you should know that

4. The “rolling HP meter” from Mother 2 is back, and is fiercely strategic this time. The “rolling HP meter” was Mother‘s great RPG innovation, and obviously the idea of a man whose calling is not videogames — a man who had written essays and novels before. It didn’t make sense, maybe, at first, because it was just kind of there. For those who came in late, it works like this: get hit with an enemy attack, and your HP starts to count down. Say you have a maximum of 100 HP, and you get hit for 200 damage. You don’t die right away — your HP counts down, instead. So mash the A button to turn the battle back around, choose a healing spell from your main character’s menu, and — quickly! — target the about-to-die comrade. When the next round comes up, mash the A button to forward through all the attacks, praying that the healing spell makes it in time. In Mother 2, the roll was a bit too fast; in Mother 3, it’s slowed down to a reasonable speed, and for quite a good reason — that is, that sixteen-hit combos take a long time to complete. Say one character is dying and is readying with a healing spell to bounce him back in this round, though the other character is currently about to begin an attack combo. You have to make snap decisions: “How many hits do I have time for?” “This enemy is almost dead, anyway? I could kill him if I score maybe 12 hits? And then the battle will be over. If I only get eleven hits before losing the rhythm, it’s the enemy’s turn, and my other party member might die and I don’t want to waste the item to heal him”. More often than not, you’ll cut the combo short. Get quick enough at navigating menus, and you’ll be able to slip in magic attacks during rounds where a character is healing himself. It’s a very curious feeling. And it’s even more curious because

5. You don’t even have to bother with the rhythm at all. Playing the battles in their awesome, rhythm-based form pretty much absolutely requires that you play the game with headphones. If you’re not wearing headphones, you might still be able to hear the music with your system’s volume turned up. Say you’re playing it on a bus, though, and you don’t have headphones. You might have a rough time. When some players first heard about the rhythm-based battle thing, they’d thought that you’d be able to play without headphones if you just memorized what music played when what monsters showed up. It’s kind of interesting to see that people would think something like that. It kind of sheds a brilliant spotlight on the lives of videogamers: in the world of videogames, we have players who would gladly play games with no sound — or, more (or less) to the point, we have games that people care to only see and read. No matter, anyway, though — if you’re not playing the game with headphones, unless you are a bleating idiot savant, you’re not going to have the beats memorized. The little trip-ups in the soundtrack — in addition to rendering many pieces of music bona-fide noise masterpieces — are simply not something the average person who would play a videogame that has music in such a way as to avoid hearing the music would be able to cope with, especially while riding a bus.

In other words, yes, Mother 3 is most certainly the work of one Shigesato Itoi, whose Mother 2‘s instruction manual began with lyrics and a request that the player sing those lyrics over the melody that recurred throughout the game’s progression. The second page of the lyrics sheet, even, included a word of caution: please play this game in stereo, because the music doesn’t sound as good in mono. The producers of this game wholeheartedly recommend stereo sound. Most players, back then, possessed stereos with auxiliary A/V inputs and monaural televisions. Itoi wanted to encourage them to do the math. Mother 3, though — it’s on Gameboy Advance. It’s all stereo, all the time, as long as the headphones are plugged in. The Nintendo DS is stereo even without the headphones plugged in — two screens, two speakers.

There are players who, in love with the music as they are, simply cannot catch the rhythm. Many friends of mine called me on the phone on the day of the game’s release. “I can’t win these battles! What the heck is wrong with me? Why am I losing? It says in the manual there’s this rhythm-battle thing — I just don’t get it!?” I had to show a couple of people in person. I felt weirdly like a god. Some people just couldn’t do it, even without instruction. My friend — he sings in an independent rock band, don’t you know — told me he had a similar experience. He had to show his girlfriend how to do the rhythm battles, and she just didn’t get it.

It’s bold, and weird, for a game to feature such a battle system and make absolutely no internal mention of it. There’s no “Super Rhythm Action!” bar on the screen during the battles. You attack, you hear a MIDI musical instrument to match your character’s personality, and you press the button again — on a hunch, maybe, if you’d never seen the manual for fear of story spoilers (hey, this is a game where the producer didn’t release any screenshots until two weeks before its release because he knew there were plenty of players like, uh, um, uh, me) — and the attacks link together.

Me, I used to play drums in a hardcore punk-rock band and I guess I can play guitar. I’ve also listened to “Race for the Prize” off The Flaming Lips’ masterpiece album The Soft Bulletin maybe about a thousand times in my life, and holy lord if those aren’t some drums — if that isn’t the kind of clang-clang that can start a train moving straight up a mountain with a summit in heaven. Maybe this means I have rhythm? I’m blushing over here, admitting that. You don’t need to be a rocker, though, to have rhythm — a guy in my office, who can’t even match ties and shirts, was able to superplay Mother 3, and the most curious corner of this is that he probably didn’t even notice he was playing the right way.

What I’ve confirmed in a half a dozen playthroughs of Mother 3, the insertcredit.com GAME OF THE YEAR, 2006, over the course of ten months during which, quite honestly, I played very little else, is that any way you play the game is the right way. If you’re scoring sixteen-hit combos at every opportunity, keeping your nose to the proverbial grindstone, you’ll possess enough money at every shop to buy the latest weapons and armor for everyone in the party, and you’ll never need to level-up, and you’ll beat the game quite far from level 99 (I won’t dare mention the holy numeral that represents the level I beat the game on, out of fear of being bludgeoned for spoilers). Otherwise, if you are blundering your way through the game and hitting enemies just once per round per character, you might end up slamming into a boss or miniboss like it was a brick wall and you were on fire. You might die. Hey, it happens. And if it happens, you’ll get a choice: continue the game, or end, and if you choose to continue, you’ll end up back at the last save point you encountered (encountered, not used), with full health and all party members revived. You’ll possess all the experience points you earned before dying, and be carrying precisely half of the money you were carrying. Since the save points function as ATMs as well, it’s pretty amazingly simple to keep your money in the bank at all times. So it is that the game remains about forward motion — it can trap you in a dungeon, with absolutely no chance or option to escape whatsoever, without a shop or an inn or anything, and it’s never impossible. It’s a conscientious move on the part of the scenario-writer (Shigesato Itoi, to drop his name again), who, yes, obviously hasn’t played very many Japanese role-playing videogames in his life aside from the first Dragon Quest, and is all the better off artistically for it. If Itoi played Final Fantasy VII, he’d probably scoff at the idea of the characters being able to sleep in an inn 50 consecutive nights despite there being a meteorite in the sky that’s supposed to fall to earth in in 30 days. Videogames — RPGs in particular — have taken tippy-toesteps away from the line of logic over the years, and there’s plenty of ridiculous all over the place right about now. Mother 3, home of some design decisions that people who play too many videogames might be privy to call “inspired”, is a refreshing change of pace, if you’re coming from games of . . . let’s say “worldlier” aspirations. Some people thought the game was thin, or shallow; as a guy who has a huge soft spot in his heart for RPGs that have towns with restaurants you can sit in and order food, I can kind of understand where they’re coming from. In a way, the king in Dragon Quest is the perfect device for adding a mega scale of depth to a game over very noble aspirations: only the king can tell you how many experience points you need to get to the next level. Seemingly, only the king helps you when you fall in battle. How do you get back to that castle? How does the king find you? If he possesses such phenomenal psychic powers, why can’t he slay the dragon himself? The world of Dragon Quest, though large, is not as large as the amount of walking you’re going to do, back and forth, between towns. The game itself provided filler-questing, trekking from town to town, to compensate for the game’s experimental nature; if the player is only defeated when (theoretically) he strays from the correct path through the game (as the proper path should only see him getting progressively stronger), reviving him at a central location is the proper way to set him back on the proper path without actually showing him the proper path. Rather, it gives him another chance to find the perfect path. Theoretically.

What Mother 3 has, however, is context: the story is written, not conceived, and so the characters always know where they are going. The dungeons are not dungeons — they are set-pieces, and they are full of battles, which are played using an in-game system that is something of a game in and of itself. The battle system is either rough or not; you either die a lot or you don’t. If you do die, you’re given a quick, fresh start, minus whatever items you’d used before dying — the “end game” option, in fact, exists in case you used an item during a battle and you want to just reload your save, so you can keep the item. You can grind in Mother 3 by wandering around dungeons and fighting monsters, with no money in your inventory, until you are dead. You revive at one of the shockingly plentiful save points, and are free to continue grinding. So it is that you can play the game like Dragon Quest — grinding and wandering and dying — though you might end up finding it a little thin if you long for exploring, and paths to stray from; or else you can play it like a rock and roll concert, winning every battle, feeling good about your performance, headphone volume on maximum, face inches from the screen.

Either way, in the end, whether you played the game the easy way (which involves lots of dying and thinking the game is difficult) or the hard way (which involves thinking the game is very easy), you will end up feeling something heartbreakingly extraordinary by the end of the story. Either way, the game is a masterpiece of flow, with regards to game design.

I am well aware that a team-mob of young men so tough they know how to use the internet would show up at my door ready to and willing to disassemble me one molecule at a time with aluminum baseball bats if I spoil a single specific story detail. I know full well that said mob would still murder me even if I tagged the story details as “SPOILERS” and printed them in black text, because they would peek just to see how much of the spoiler text is, say, introductory stuff like “So, at the beginning of the game”.

And even then I would understand their curiosity; I awaited Mother 3 for a long time, like many Beach Boysophiles awaited Brian Wilson’s SMiLE. (Well, maybe not that long a time.) I wouldn’t want to spoil it for anyone, I suppose. Either way, here I am, giving you a warning: depending on precisely how large of a percentage of your nightly conversation with your chosen deity you devote to asking for the Mother 3 English translation patch to be released tomorrow, you may or may not consider some of the following — which will strive to remain as abstract as possible — to be a spoiler. Rest assured that if you want to play Mother 3 because you love Mother 2, then you will enjoy it when you do, so don’t feel compelled to read a review merely to make up your mind. You’re the kind of person who’s better off just looking at scores, then, anyway. And yes, the score of four stars listed above is the highest possible score. Yes, four out of four, not four out of five.

Anyway.

Shigesato Itoi apparently wrote the whole scenario of Mother 3 in two weeks. He had originally written it nine years before, and then decided to rewrite it to ensure its freshness. The game had originally been somewhat deep into development for Nintendo 64 before hitting some odd snag or another; Itoi himself would later say that he wasn’t satisfied with technical aspects of the game. Graphics and stuff. The way the music sounded. Years passed. During a taxi ride from Nintendo headquarters to Kyoto Station with legendary game creator Shigeru Miyamoto and Nintendo president Satoru Iwata, he was asked if he would consider moving the game development to Gameboy Advance. He’d been in the Nintendo headquarters for something of an important meeting; what was being discussed in the meeting, Itoi has never mentioned, even on his blog. I’m guessing it had something to do with Nintendo DS — which had just been released at the time — or perhaps they were briefing him on the then code-named Nintendo Revolution. Nintendo was, at the time, facing the reality that the Gamecube was a hit with only gamers, because it made games that appealed mostly to non-gamers. They were trying to get their heads around that, and they’d eventually produce a videogame system — the Nintendo Wii — that appealed most strongly to non-gamers. At the period in time when the magical taxi ride occurred, Nintendo must have been fielding the opinions of their most historically trusted non-gamer collaborators. Shigesato Itoi is definitely the most proficient of those collaborators: not only had he written and produced Mother and Mother 2, he’d also thought up the name for the Gameboy. (Looking back on it, it’s an obviously play on “Walkman”.) (Looking back on it further, it’s kind of funny that Sony USA suggested to call the PlayStation the “Gameman” because “Play” didn’t sound cool enough.) (Looking back on it again, the “PSP (PlayStation Portable)” is really a dumb name for a videogame system — a station (as in, something stationary) that’s also portable? Sony could use a Shigesato Itoi, I reckon.)

Whatever happened, Itoi’s interest in games was rekindled. He began blogging somewhat fiercely about the Nintendo DS and how brilliant it was. He released Mother 1+2 on one Nintendo Gameboy Advance cartridge, after inviting readers of his website to write in detailing their memories of either game. (My letter got featured on the site. I nearly exploded.) After years of joking vaguely that he was considering releasing Mother 3 on Super Famicom, he announced that Mother 3 was in development for the Gameboy Advance. Which was, essentially, the same thing. Weirdo conspiracy theorists somewhat like myself harbored a whispered hope that a Super Famicom version would actually be released, primarily because that would be hilarious and secondarily because it would be amazing — it would represent the longest gap yet between the death of a videogame hardware and the release of an officially approved game.

Yet, after announcing that the game was on the way, all went silent. We didn’t hear a thing out of Itoi concerning the game for a long time. I spied him in attendance at the Nintendo Revolution (later to be called “Wii”) controller unveiling in Tokyo in September of 2005, clapping along with everyone else. Dragon Quest series producer Yuji Horii gave a presentation on the elegance of the controller, and I’m sure that his enthusiasm was Itoi’s enthusiasm (after all, Itoi had once jokingly referred to Mother as “Dragon Quest with different graphics”). It’s safe to say that Itoi is probably considering making something for the Wii. It’s also safe to say that his passion to make something new also endowed him with a quiet and fierce need to finish what he had started in the past.

Itoi would later say that he approached the writing of the scenario as though he were writing a play. Whether he meant this creatively or literally, the comparison rings true. Plays are stereotypically things written in seclusion following an emotional event, and surely enough, Itoi had just been through a rather long, slow divorce when he holed himself up for two weeks to pound out the script. And the finished product even flows like a play — it’s divided into acts, which progress chronologically, jump playfully from character to character, and succeed in telling various angles of the same small story as it progresses over time. The original Mother was based on a novel, and flowed like a novel; Mother 2 was an original story, tailor-made to be a role-playing videogame; Mother 3 succeeds as an original story on the one hand because at its outset it’s so drastically far from Mother 2 in terms of setting and mood, and on the other hand because it really, uncannily does come to feel like a long night at the theater. The small, intimate, evolving setting of the story — as opposed to Mother 2‘s selective world-spanning — comes to feel like an elaborate multi-layered stage in a modern theatrical production. At many points in the game, a “dungeon” will consist of less than a handful of screens; a “fetch quest” might involve less than a hundred in-game steps. There are parts where you have to travel from one side of the stage to another, and those times usually use vehicles in which you’ll encounter no enemies. There’s shockingly little waste or wallowing; as I’ve said, the game has an agenda.

For a large portion of the story, there is no main character. In the beginning, acts and scenes of the story will open with a different character in the lead. Eventually, everything comes together. There’s some utter silliness in the story, some ridiculous moments, some questionably weird parts expertly inserted to throw the player off, and then there are huge, earth-shaking, punctuating moments of drama so poignant they can’t be accidental. Playing through the game in its native Japanese is something of an amazing experience for the most open of minds. Many might wonder why an official English release hasn’t been announced, and immediately conclude that it’s because Nintendo of America is stupid. In reality, it could be much more complicated than that. For one thing, this game tells a story using colorful little hand-drawn cute cartoon characters. It is not, however, a cartoon-character story. It brims with allegory critical of events as current as 2006 or 1986. If the game were a genre of music, however, it would be jazz blues; played by a single acoustic guitar, slowly, any moment of its progression can enthrall a listener who didn’t expect to walk into a room and hear live music being played by a live individual. However, jazz blues can’t break down and end naturally. It’s music where every moment sounds like the beginning of the end. It can be started out of nowhere — you could open a box, and hear it, and not be offended — and it can end at any given second. It either stops on any given note played normally or walloped. So it is that the uninitiated listener will hear jazz blues being played and find it pleasant, though after its bounced around for long enough, he will imagine, without imagining, that this experience will not end satisfactorily. When the Real Story is introduced into Mother 3, and when What Must Be Done is outlined, as the story continues along the same path, suddenly the unchanging, whimsical appearance of the game becomes something fearsome. When the moments of revelation begin to slip in, and when the hard feeling starts to happen, there’s no saving the player. Mother 2 went out with a bang and then a hum; it whipped an orchestra into a crescendo and then let the player go out to dinner with the entire world when all was said and done. Mother 3 is playing with more a delicate environment and, to put it simply, the story, at times goofy or benevolently over-the-top nonsensical, plays with real emotions so subtly that by the end it manages to make you actually feel a real jealous rage. As a work of theatrics, it’s effective because it’s cathartic; as a videogame, it’s effective because it’s intimate; as a piece of entertainment it’s probably not something that someone could be completely truthful about and still recommend for release in English.

Put quite frankly, the game is closer to literature than Mother 2, even if it’s not as life-changingly amazing an experience in 2006 as Mother 2 was in 1994. This makes it, either way, by default, the closest a videogame has yet come to modern literature (albeit of a slightly absurdist variety). As a 27-year-old in 2006, however, Mother 3 no doubt meant as much to me as Mother 2 did to a fifteen-year-old in 1994. The goofiness of the story is amplified, and a little forced; it’s as though Itoi worked the goofiness in conscientiously, aware as he was writing that the characters in the game would look like cute little cartoon characters. Ironic that he’d originally given up trying to make the game in 3D because it didn’t look right, longed to do it in simple hand-drawn 2D, and then ended up straining himself to punctuate the story with enough lighthearted moments to not feel like a wake.

At the core of this noisy, funky, jazz-bluesy literesque pastiche, we have psychic drag queens versus an army of pig-mask-wearing goofy soldier men from whereabouts unknown. Behind all this, there’s a theme of capitalism’s arrival to an island nation that has never known the concept of money. There are sinister deeds, a bad guy, monsters, and heroes, though all of it is subdued and unabashedly intelligent. The story comes off as pseudo-literature thanks to, as in Mother 2, Itoi’s non-game-producer’s outside-the-box grasp of game design principles, which allows him to celebrate the art of story-writing because of the media. Though his ambition, this time, is far more reined-in than in Mother 2. He has a clearer agenda this time than to “mess with the player” — no, this time, he’s trying to tell a deeply personal story. Most of the game’s setting, surroundings, mystique, charm, and flow is filler when you consider the motivations of the emotional engine of the story. Remarkably, Itoi has written a videogame that, if not necessarily literature or art, is very clearly excellent fiction. And as fiction, it’s very masterfully presented, right down to the meter of the lines — you’ll occasionally see entire passages in seven syllables per line (seven being something of a magic number for syllables in Japanese: the middle line of a haiku, for example). And as always, Itoi’s trademark sentence-structure-play, which has graced many a movie poster over the years, delights again and again, whether it’s popping up in the short disposable monologues of townspeople or rarely appearing in the middle of a long, significant conversation. (Itoi’s famous slogan for Hayao Miyazaki’s film “Kiki’s Delivery Service”, “Ochikondari mo stuffa kedo, watashi wa genki desu” — “I was a little depressed for a bit; I’m okay now” — is parodied at one point, even: “Kietari mo stufferu kedo, watashi wa genki desu” — “I’m disappearing a little bit; I’m okay, though”.)

In other words, well, words are very important to Mother 3. Words are at its core; words are its pride and joy. Translating it would, according to a dictionary, involve changing all of the words to another language. There’s a chance the words could be wonderful in English; after all, English is the language of Shakespeare, and the Bible (according to Henry Higgins). However, in the realm of games, where there are very often text-compression issues when translating from Japanese into English, what are the chances a translation of Mother 3 could be as free-wheeling and humorous as the Japanese version, while still retaining the dramatic weight where it counts? Mother 3 is as meticulously balanced as a narrative as it is as a videogame; it is balanced in only the way that something written in a single, emotionally-charged, secluded state by a single (and recently divorced) individual can be. It’s a snapshot of a brainstorm. Translating it would be like making a painting of a photocopy of that brainstorm. You’re bound to lose something, and if it loses something, it’s not perfect. For example, have you ever read Japanese or Chinese poetry in English translation? Line lengths all distorted all over the place; it’s not worth it, jack. It’s really not. In Japanese or Chinese, that stuff is perfect. There’s a reason they call it poetry.

There’s a reason they call it poetry.

There’s a reason they call it poetry.

See, that’s a perfect sentence for rhythm — ten syllables. I had to think that one through for about a minute. Is Nintendo willing to spend one man-hour for every sixty lines of text in Mother 3?

Or maybe the game isn’t being translated officially because of the psychic drag queens and the blatant socialistic allegory. If the game didn’t star exclusively cartoon characters, such free speech might even be welcome in America, I’d imagine. Doesn’t everyone over there hate the president by now? Those people are a good enough audience for Mother 3. Or Europeans; I reckon the dialogue would work in French. The French, at least, would get it.

So yes, if you want to be optimistic, you can say that the respective English-native Nintendo corporations are merely being conscientious about releasing the game because it’s too good.

Good writing in Japanese videogames, though — who would have imagined it’d come to this? With the dissolution of Square-Enix into the zippers’n’pleather of Kingdom Hearts, with their company’s reputation just about destroyed in Japan because they released a masterpiece (Final Fantasy XII) and no one seemed to notice, those who would challenge their faltering dominance, rather than merely push for bigger and more brightly colorful, have extended their hands toward the literature on the top shelf; their medium is yet a child, though it is snot-nosed, resourceful, and willing to stack boxes on chairs to get what it wants. Miyuki Miyabe, a world-class Japanese fiction-writer whose prolificity knows few bounds — she writes literary fiction, romantic comedy, high fantasy, high sci-fi, and hard-boiled mystery novels with a master’s grace — also happens to be a devoted enough game fan to have written a poetic fantasy novel based on the spare story from the videogame ICO. She followed this up with a novel, Brave Story, about a young boy on an adventure to save his dying mother; the boy travels from the real world to a fantasy world where the people are accustomed to the appearance of “travelers” who fall from the sky and are always headed in the same direction. It screamed to have a game series made out of it — and it ended up becoming three games in one instant, though only after becoming a comic book series and then an animated movie. The PlayStation 2 and Nintendo DS games were pretty tepid; the PSP game was white-hot. With a simple scenario adapted from an original story by Miyuki, based in the universe of the original novel, and simple, refreshing gameplay concepts spawned by Yoshiki Okamoto, who had made Street Fighter and Onimusha, the game ends up, right down to the very last detail, a tribute to 16-bit Japanese role-playing games for the Super Famicom, delivered fresh from people who you never would have imagined harbored any love at all for the genre. On the other hand, you’d have no reason to suspect that they hate the genre, either.

The music was perfect. Like a Nobuo Uematsu cover band that decided they were good enough to write their own songs. The same could be said about the game itself — the battle system was covering Dragon Quest so perfectly it became better than Dragon Quest. The simplicity of the combo system, where your attack power grows with each successive attack, so long as your character does nothing aside from attack, was absolutely brilliant.

Likewise, when Media Vision set about making Wild Arms V: The Vth Vanguard, they decided to hire an actual novelist, one Kaori Kurosaki, to write the scenario. She was easily more involved in Vth than Miyabe had been in any of the Brave Story games, insisting on a branching narrative because, as she said in an interview, there just wouldn’t be any other way to keep a videogame story actually interesting. Many fans of the series, as fans would, objected to the idea of change. The writers insisted in Weekly Famitsu that they had wished, ever since the first installment, to hire a writer to work on the series. It was just never in the budget; the urgency was never there; the world had been content to play games with stories written by people with computer science degrees. What’s nice about computer scientists is that, if they’re personable enough to pass a job interview, they normally have exception — if somewhat obsessive — grasps of logic and common sense that, when lent to a narrative, make sure things always come around full-circle. Sometimes they don’t succeed in communicating any heart, though. And usually, they’re thinking of the game design and the story simultaneously. They’re thinking of reasons to get the characters into a spaceship so there can be an action scene on a spaceship, because they’ve already got a spaceship environment half coded, et cetera. When you get a writer who comes from outside the game field, they might end up constructing a story that will present design challenges. Kurosaki, in her Wild Arms V scenario, for example, makes it the goal of the first “dungeon” to escort your female childhood friend to the place where you first met (sort of) so you can tell her that you’re planning on leaving the village. In other words, it uses characters’ emotions as a goal for an in-game task. It’s subtle, though hardly invisible: the story and the game design are rubbing against one another, and creating emotive friction. It’s nice.

I’d like to think there are many writers or artists out there who could write videogame stories that would end up teaching design teams more about their work than their job ever could — the problem is finding which artists would be willing, and then approaching them, or waiting to be approached by them. I wonder how long it’s going to be before Stphen Drozd and Wayne Coyne of The Flaming Lips are asked to write a videogame concept and provide its soundtrack. I’m sure something amazing would happen. (Note to self: delete this sentence before publishing this review again.)

Itoi’s genuine, curious interest in the medium and hands-on approach is expressed perfectly in Mother 3. While writing the scenario for Mother 3, he no doubt was always aware of exactly how it would play as a videogame. He knew he was making a game for a portable system; he knew the story would have to be digestible in small bits; I’m sure he also predicted that, one night in April of 2006, his scenario would result in a 27-year-old man missing the train stop where he lives, getting off at the next station, and continuing a particularly pointed conversation until it was safe to save the game, descending a real-life staircase, and then ascending to a platform for a train going back in the direction of home. Itoi is more than a mere writer of a game’s scenario — he’s aware of precisely how the game will play. He put in enough gameplay and scenario quirks to nearly disqualify the game of the nastier ramifications of the “RPG” genre distinction.

There is scarcely any adventuring, and very little dungeon crawling. In fact, the longest dungeon in the game, which might take you an hour, can be completed in less than three minutes if you’ve ever heard a certain song by Japanese pop-rock band Spitz. (I’m not going to bother to explain that. You’ll have to take my word for it.)

Characters will occasionally, at seemingly random moments, become “feverish” while walking. The “fever” will continue for a while, during which you cannot use the running ability to travel around the world map. Running is useful in more ways than speed: if an enemy is weaker than your party, you can run right through it, defeating it instantly (yet earning no experience points). Frequent occasions when a character is “feverish” will no doubt frustrate you at first — however, when the feverishness ends, the character who had been dragging the party down earns a new psychic skill. This is how the majority of the skills in the game are earned.

Sometimes you’ll open treasure boxes, and there’ll be nothing inside. Maybe there’ll be a reggae beat, or a samba beat.

In a move very similar to the “coffee break” one-third of the way through Mother 2 (which sincerely invited the reader to have a cup of coffee and reflect on the events of the game thus far, and know that there is about twice as much of the game left), Mother 3 positions the absolutely shortest act of the game directly before or after (spoiler-guarding here ITVGR) the longest one. The shortest act is textless, wordless, musical, and meaningful. The abundant joy and crushing sorrow of Mother 2 has grown up. Itoi’s stern affection and scrutinizing semi-ignorance concerning the media of videogames has blossomed, and I would dare say that he’s hit upon the precise form of game he intends to make more of.

To turn this into a game review for a moment, let me just mention, as a kind of aside, that the biggest problem with Mother 2, that being the delay on the menu cursor, has been fixed. The cursor moves wonderfully. The fact that equipment, item, and status menus have their own music is very clever, though it initially detracts from the experience of people wanting to listen to the overworld music while navigating menus. Then again, the game is not about menus; the music enforces this. The text being displayed entirely in hiragana, while helping the meter and rhythm of the game’s wonderful dialogue more apparent to the player, still retains the curious tendency to force players to move their lips while playing. A week after the release of the game, I saw a girl moving her lips while playing a Gameboy Advance SP, and I was fairly certain I knew what game she was playing. At any rate, the text is now displayed entirely within a black bar on the bottom of the screen, maximizing the width of passages and enforcing extreme readability; it’s exactly how I’d wished it would have been displayed in the Mother 1+2 re-releases. It’s very welcome.

The developers at Brownie Brown deserve a medal for making everything work precisely as it must have appeared in Itoi’s head while he was working on the scenario. There are no regrets that this game is portable. It looks perfect, just as Mother 2 looked perfect in its day and looks more perfect now. Reviews at the time of Mother 2‘s release had compared it totally unfairly to the more realism-aspiring Final Fantasy VI, which, even then, had been pining for computer-generated cutscenes (in a quaint way, yes). Mother 2 and Mother 3, along with killer 7, are games that share a unique honor of looking exactly as the creators must have intended. Mother 3, especially on a Gameboy Micro (damn these eyes of mine for not being able to read the text), looks silken and perfect; on a DS Lite it’s lordly; on a Gamecube Gameboy Player run through progressive scan, it’s pornography for pixelantes. Dynamic scenes involving vehicles or high-speed travel involve locales so ingeniously planned that, were they instead rendered with Super Famicom graphics on a PlayStation 3, would still delight any viewer with the right kind of imagination. There’s no shame in this being a portable game; years may pass by, and Nintendo might release a newer DS with even brighter screens and better graphics; we might, someday, see an RPG by Shigesato Itoi with fully hand-animated characters and voiced dialogue. Though Mother 3 is essentially perfect for what it attempts, I can’t by any means say I would not be fiercely looking forward to any videogame Itoi intends to put his name on in the future. All I know for certain is that there will be more. Maybe not of the Mother series, though definitely of something else. If there’s anyone in the world who would be immune to the sequelitis plaguing videogames, it would be Shigesato Itoi.

Here, I lament my inability to severely spoil the game. And simultaneously, I pat myself on the back for not getting close to touching the game’s main plot points with even a fifteen-foot-pole.

One thing sticks out in my mind the more I think about the game — as the protagonist changes with each chapter, and the central story is revealed to be deeper and deeper, as the quiet awe and dread begins to set in, I can’t help being impressed by one particular technicality. That is, the fact that when the character assuming the central role changes with each chapter, that character becomes a mute. At first, I’d thought this was something of a kooky throwback to old role-playing game conventions: the main character in Dragon Quest doesn’t ever speak, for example, because Yuji Horii wants the player to imagine the main character’s lines for himself. In Mother 3, there is another, deeper motive for this — or so it might seem. The further you play into the game, the heavier the emotional weight becomes when the character who was a mute in the previous chapter appears and speaks his first lines in the current chapter. There is nothing more poignant in literature and theater than a depiction of silence; second to the depiction of silence is the moment when the silence is broken. Mother 3 sets silences up like dominoes, and when it dramatically flicks a domino down, and that domino hits the domino before it and stops dead, every single time it feels like a milestone. Again, I applaud the game as “excellent fiction”.

Thinking about it enough to write about it, I realize that this dramatic quirk of Mother 3 is in fact haunting me in a sinister way. In fact, I realize that it very much is a theatrical aspect, not a cinematic one or a literary one or a game-like one. Thinking of this, why, perhaps the most striking reason why Mother 3 feels like a “play” has just occurred to me: you can see the entirety of the characters’ bodies at all times during dialogue scenes. Or maybe not — or maybe so. After a few months during which you’ve only watched films in cinemas, when your imagination has atrophied to the point where I can’t passively imagine an actor speaking slowly in any view other than a close-up, when I make a rare night out to the theater, one of the first things to strike me is — beyond that those are actual people up there — I can see the actors’ whole bodies. There was a time when I studied stage acting, I’m not even kidding; the teacher’s enthusiasm for the same full-body warmup exercises every day was exasperating. Maybe she was faking it. She was, after all, an actor.

Silent characters speaking suddenly; I can imagine this in a modern play. An act begins with a scene frozen in time, and a character spot-lit. The spotlight holds for thirty seconds. The stage lights come up full. The characters begin to move; our eyes naturally follow the character who had been bathing in the spotlight. The other characters speak their lines, play their parts. When act two begins, the spotlight is on another character — and it’s the same setting as the previous act. For this act, this new character is silent, though halfway through he or she runs into the character who had been silent in the previous act — just as the previously-silent character had run into the now-silent character in the previous act. Only now, the one who had spoken is silent, and the one who had been silent is speaking. Five acts, a full story, and at the heart of it, five short conversations; by the end, we have heard both sides of every conversation, though never as they would have naturally occurred. Except for one — there is one side of one conversation that we never got to hear. We don’t even think about it until we’ve gotten home, slept, eaten breakfast, and been asked twice how the play was last night.

This sounds like something Hideki Noda would probably write. I wonder.

In December of 2006, thanks to a friend who had a friend who designed the stage, I had the opportunity to see Mr. Noda’s play latest play, “Rope”, at the Shibuya Bunkamura theater. “Rope” is a story of professional wrestlers. Kind of. The stage was a wrestling ring, from which characters will occasionally exit to stand before the audience and . . . be themselves. And there is a girl, who may or may not have traveled from the future, who lives only outside the ring.

Mr. Noda said in interviews that the play is his analysis of the post-9/11, post-YouTube world, in which people’s lives are becoming synonymous with entertainment. The idea for a play in which characters behave differently inside the metaphorical “wrestling ring” and out first occurred to Noda when he heard Japanese office ladies on a lunchbreak watching footage of the airplanes crashing into the World Trade Center back in September of 2001: said one lady to the other, “It looks just like something out of a movie.” I painfully knew where he was coming from, and, personally, have attempted to tackle similar themes in my own fiction: take, for example, my ex-girlfriend, who had been my best friend in the world for years. She giggled at our first kiss, and I thought with a thick twinge of self-embarrassment that it was a lot like when Ross and Rachel first kissed on “Friends”, and Rachel laughed and said it was like she was kissing her brother. When we discussed the incident, weeks later, it was her to bring up the Ross and Rachel comparison, and I felt a great G-force, like a rollercoaster hill, like the floor of the world falling out from beneath me. This was in June of 2001, anyway, so I reckon my inspiration beat Noda’s. Still, I also have to reckon that he’s better at being inspired than I am.

Avid fans of Noda’s plays other than myself include Shigesato Itoi; he reportedly goes to see the ones he likes the most as many times as he is able to secure tickets. I’m told he was very pleased with “Rope”. (If you happen to be in London, I imagine he’ll be doing an English run of it this year, so do check it out.)

In August of 2004, I was in attendance for the opening night of the English-version revival of Noda’s play “Red Demon”, in which Noda played the title character. Noda had played the male lead in the Japanese version; though he’d written the English script, he apparently wanted to play the character with no dialogue. The “Red Demon” is a man who washes up on a shore in a simple, dead-boring little island town in the middle of nowhere. He does not speak their language; he only makes sounds and flails around. He is not red, and he is not a demon, still, the people call him a “Red Demon” because they don’t understand anything about him, and they especially don’t understand how little they understand him. He’s locked up and persecuted; the people are afraid the “demon” will eat them. There’s a girl who takes pity on the “Red Demon” and tries to free him. The story somehow manages to come to the conclusion “Demons don’t eat people: people eat demons, until there are no demons.” And then we continue to expect there to be demons. It’s a rather thin little theme, smooth as a pebble; the lighting was pretty; I was greatly entertained.

I was urinating during the intermission in a toilet too far from the theater to be comfortable. The toilet was sparkling clean and dead empty. As I finished my business, a Japanese men strode up next to me. I washed my hands, taking my time. I splashed some water on my face and dabbed at it with a paper towel. The Japanese man came up and used the sink next to mine. I saw his face in the mirror. It was Shigesato Itoi.

I really wanted to say something to him, I’m not even kidding. What do you say to someone in a situation like that? “I’m really looking forward to Mother 3.” The game’s scenario hadn’t even been written, then. If I’d have said that, he’d probably have looked at me and said “Yeah, so am I.” Or he might have just said nothing at all.

EXTRA BONUS PARAGRAPH. Hello and welcome to an extra bonus paragraph, written in celebration of Mother 3‘s induction to the Action Button Dot Net Manifesto Hall of Fame. Many emails have flown into the Action Button Dot Net Citadel’s chimney these past few weeks; some merely ask what #1 is going to be; some present conspiracy theories indicating that there aren’t enough actually great videogames left for us to possibly fill out the top slots, concluding that we’re going to deliver some cop-out like “jerking off” as our #1 choice. Many others ask if we’re going to have the balls to include both Mother 2 and Mother 3. It’s somewhat flattering that you’d ask that. You’ve obviously caught on that we’re not above including two games from the same series, even though we, to this point, haven’t yet included two games from the same series. We do not pick Mother 3 over Mother 2 because Mother 3 fills some kind of quota for our list. No, we pick it because it, more than Mother 2, is the kind of game we seek to celebrate on this list. It is tight and focused, with inobtrusive mechanics and genuine confidence in its plot. The mechanics melt into the game’s facade. You hardly notice that you’re playing an “RPG”. That you’re telling dudes to attack other dudes by selecting “fight” from a menu. It’s a fluid experience.It flows right through you from the beginning to the end.

EXTRA BONUS PARAGRAPH. Hello and welcome to an extra bonus paragraph, written in celebration of Mother 3‘s induction to the Action Button Dot Net Manifesto Hall of Fame. Many emails have flown into the Action Button Dot Net Citadel’s chimney these past few weeks; some merely ask what #1 is going to be; some present conspiracy theories indicating that there aren’t enough actually great videogames left for us to possibly fill out the top slots, concluding that we’re going to deliver some cop-out like “jerking off” as our #1 choice. Many others ask if we’re going to have the balls to include both Mother 2 and Mother 3. It’s somewhat flattering that you’d ask that. You’ve obviously caught on that we’re not above including two games from the same series, even though we, to this point, haven’t yet included two games from the same series. We do not pick Mother 3 over Mother 2 because Mother 3 fills some kind of quota for our list. No, we pick it because it, more than Mother 2, is the kind of game we seek to celebrate on this list. It is tight and focused, with inobtrusive mechanics and genuine confidence in its plot. The mechanics melt into the game’s facade. You hardly notice that you’re playing an “RPG”. That you’re telling dudes to attack other dudes by selecting “fight” from a menu. It’s a fluid experience.It flows right through you from the beginning to the end.

It’s safe to say that the plot is the “point” of Mother 3. We have, in this list, celebrated games like Half-Life 2, where the plot is married firmly to the flow of the visuals and, in some cases, the game mechanics themselves. Some games are plots that you “play”; Mother 3 is a plot that you “experience”, though it remains an excellent videogame from start to finish because it never feels like it doesn’t belong to you. One of the things we don’t like very much in videogames in general is when they make light of videogame conventions for the sake of getting a news post on Kotaku; meanwhile, Mother 3 threatens several times to turn in on itself and close up. Its characters become entirely caught up in the history of this particular series of videogames. Yet this only adds a new layer; if you’re viewing it as an outsider, we can only envy you.

Now, for some bad news: we have very recently heard, from a very reliable source, that this game will never be officially published in the English language. The developers themselves commissioned full English, French, Spanish, and German translations of the game for the purpose of communicating it to Nintendo of Not-Japan. It did not pass their quality examinations. According to our source, the plot was “too serious”, to a point betraying the graphic design (cartoon-like). There you have it: Nintendo, champions of the everyman, flag-bearers of the non-gamer, proponents of “change”, have paid a kill fee to a small game developer in order to guarantee that their “too serious” game with literary themes will never be published in the English language. We won’t sling mud at Nintendo; you can do that yourself. We will, instead, say that it’s probably not their fault. You’ve no doubt seen the controversy that erupted all over Fox News when it was discovered that you could gayrape alien childrenin Mass Effect with the press of a single button ; imagine what they’d say when Nintendo published a cute cartoony game that brainwashed kids into believing that Communism is a good idea. The American media is a dense and dull game of Telephone: they’d probably end up switching “Communism” for “Facism”, and by the time a TV news story aired, Mother 3 would be a videogame about a charismatic monkey rescuing Hitler and curb-stomping Ronald Reagan.

What we’re trying to get at here is: you. People who have been working on that English patch for the ROM: go ahead and give this game to the people. Of course, we won’t play your translation, because we already played it in Japanese, which, yes, we understand, like every other metrosexual power broker here on Wall Street. Speaking Japanese comes as naturally to us as wearing suit jackets cut just above the belt, thank you very much. Anyway. You have The Action Button Dot Net Blessing. Do with it what you must.

–tim rogers

Pingback: inazuma eleven (***1/2) | action button dot net

Pingback: Shigesato Itoi’s MOTHER 3: A Literary Videogame | Ekostories