a review of Castlevania: Bloodlines

a review of Castlevania: Bloodlines

a videogame developed by Konami

and published by Konami

for Sega Genesis and Sega MegaDrive

text by tim rogers

Castlevania: Bloodlines is the best Castlevania game, and the best side-scrolling “beat-em-up” action game in history, if we had to pick right this moment. Why someone would think they prefer another side-scrolling action game is easy enough to understand — maybe they don’t like the goopy-gory schlock-horror theme of Bloodlines — though why anyone would prefer another Castlevania game is an unsolvable mystery. Some people say they like Dracula X: Rondo of Blood for the PC-Engine CD better, because it’s more rare, or that they like Castlevania: Symphony of the Night better, because it’s “epic”; some people stoop to say Castlevania III: Dracula’s Curse for the NES is the best in the series, because they’re in-touch with the “old-school”. I have been, in truth, for the longest time, one of those people who will just claim whenever asked that I prefer Castlevania III, though I’m really only ever just posing. I’m willing to confess to my own posery — and not only that, I’m willing to fully pardon anyone who has ever failed to precisely acknowledge that Bloodlines is far and away the best game in its series. It’s archetypically great; every human being knows it, whether they’ve ever played it or not.

Castlevania as a series has never actually been about internal consistency, much as the current state of the games would slyly have you believe otherwise. In recent years, series helmsman Koji “IGA” Igarashi has tried as deadly-seriously as possible to glue the plots down to rigid canon structures, making sure everyone in the audience knows exactly whose father / sister / benefactor was killed by which demon / succubus / bone-throwing-skeleton. Looking back at the series though, it’s painfully plain and simple to see that any hopes of “continuity” were hecked from the start with a boomerang made of bat wings. For one thing, the games simply can’t agree on a title — the first game in the series was called “Demon Castle Dracula”, with foreign titles ranging from “Dracula’s Satanic Castle” to “Haunted Castle”; in Japan, the sequel was called, quaintly, “Dracula II”, and the next sequel after that was called, roughly, “Legend of Dracula’s Castle”. The “Castlevania” moniker has only ever been ever-present in America; in Europe, they went so far as to call the first game “Vampire Killer”. The “Castlevania” series is a classic example among Japanese games industry elite agents of how not to package a franchise. It could very well be one of the shortlisted reasons that Square will never stop putting the “Final Fantasy” name on more than a dozen products a year: in Japan, Konami’s clueless code-jockeys would eventually go so far as to throw away the closest thing they have to an iconic name (“Akumajou Dracula“, “Dracula’s Demonic Castle”) in favor of an unwieldy katakana version of the English name: “Kyassuruvania“. Prior to this, they had tried twice to spice up the name of the series, maybe making it sound something like a super-avant-garde robot anime: “Dracula X”, the Super Famicom remake of which was called Dracula Double X. When the time came to strain out another PS2 game, they flipped the title back to Akumajou Dracula.

The contents of the games were never even in agreement, which, in retrospect, is actually cuter than a barrel of baby chimps (note: unlike in reality, the baby chimps would be nonviolent and not at all bloodthirsty). The soul of Konami’s first Dracula-slaying game lay in how it relished in schlock horror, with a flickering film-window title screen with little dust flecks on it and everything. Castlevania was about locomotion, about pumping forward. It was made because Konami had read The Declaration of Independence penned by Shigeru Miyamoto’s Super Mario Bros.: “We hold these truths to be self-evident, that Videogames are created Awesome . . .”

Konami’s boys wanted to throw together an action game with weapons and edge; it is with a palentologist’s interest that I look at Castlevania and determine in a split-second why it’s steeped in gothic-horror imagery: because the music is hecking great. Having recently messed with Famicom sound chips on a stupid whim, I can say that “madly pounded pipe organ” is pretty much the easiest voice to accidentally end up with. I’m hardly even joking here — the sound team, made up of dudes who had never predicted that loving Ryuichi Sakamoto and the Yellow Magic Orchestra would eventually grant them a nine-to-five job, were no doubt balls-to-ceiling ecstatic about the melodies they hammed together, so ecstatic that they didn’t stop to think “Why does everything sound like a pipe organ?” The game designers only wanted some excuse to have button pushes translate into attacks focused on moving targets which would then die and allow the hero to continue pumping forward. The designers and programmers no doubt had some idea about the friction and the weight of the game they wanted to make — where Super Mario was Parkour The Game v0.1, about freedom and momentum and fabulous, flamboyant jumping, Castlevania would be about moving precisely and attacking accurately, about sparring and boxing with every respective fearsome enemy. It would be about forward motion and surmounting giant, conceptually interesting boss characters. That the music sounded like an organ spurred them to make the boss characters horror movie monsters. Think about it: it’s probably impossible for them to have made a game featuring such a hilarious mishmash of horror monsters unless no one on the team gave two stuffs either way about horror movies. The only thing that seemed to have been set in stone before the visual design began was “guy climbs stairs, swings a whip”. They obviously wanted it to be a whip. When the game’s fate as a horror film pastiche was determined, that’s when the in-joking began. So this guy’s killing Dracula, yeah? With a whip? Why not make it so the whip is the only thing in the world that can kill Dracula? Why not call the whip the “Vampire Killer”? So the snowball of stupidity began rolling.

It worked smartly enough, for something so meatheaded: the horror backdrops, for the most part, were researched nicely and cute enough to warrant multiple admiring playthroughs. The sound was spectacular. The game’s friction was tight with snaps and crackles. Of course, it wasn’t perfect, though since it was a moderate worldwide commercial success, someone at Konami was obligated by job title to consider it perfect, and so the “series” was born. It was only around the time the sequel, more of a non-linear Zelda II-style adventure, was released that kids on playgrounds began whispering about this awesome series. “You’re a dude with a whip and you fight Frankenstein and werewolves and the Grim Reaper and even Dracula!” “Can you swing with the whip, like Indiana Jones?” “Yeah! And at the end, Dracula turns into a giant bat monster!” “You liar, Dracula doesn’t turn into a giant bat-monster!” I personally was disappointed, eventually, when you couldn’t use the whip to swing like Indiana Jones, though I got over it by the time Castlevania III, a slightly linear action-adventure, was released, and featured a character that could climb walls.

Eventually, as the series would prove wont to do, the designers plotted out a remake of the original — hero Simon Belmont attacking Dracula’s castle, now with Better Graphics and Stereo Sound. The game was called Super Castlevania IV in America, and simply titled Akumajou Dracula (again, “Dracula’s Demon Castle”) in Japan. In Japan, it was clear that it was a remake; overseas, it left people wondering what had happened to Ordinary Castlevania Four. The remake tooled around on deep-reaching levels with the core idea of the game. It controlled and flowed differently — this was, of course, the point. They only made the game about a man with a whip — now finally able to swing around like Indiana Jones — and a castle and Dracula because people recognized the theme by now. They made the graphics as huge and the music as gigantic as possible. For years, at this point, kids had huddled around multi-player arcade brawler cabinets and relished the graphics while forgetting that the gameplay didn’t exist. Castlevania IV was an effort to stuff gamplay and spectacle together into a linear singleplayer experience, and it was probably the last time the Castlevania series producers understood their market perfectly.

(Pause to reflect on the recently-announced Castlevania: Judgment Devil-May-Cry-like one-on-one 3D fighting game, which will probably be brilliant: the producers now understand the audience, though the audience doesn’t understand the game. One commenter on Kotaku.com said, of the character designs, that they’re “too girly”, and that “they should bring back the guy who designed the characters in Symphony of the Night” (which was a girl (who drew even more girly men). It’s ship-abandoning time, kiddos.)

1993’s Dracula X: Rondo of Blood for PC-Engine CD was a throwback to the old-school Castlevania controls, with new-school graphics, hardcore rocking audio, voice-acting, and some thrilling half-motion video. What had brought it about in the first place is a mystery, though looking back from a decade and a half later, it’s pretty obvious that someone had the idea that the Super Famicom Castlevania remake wasn’t particularly the correct direction for “evolving” the gameplay — which, remember, is the only thing the series had ever been about. Dracula X was several steps back and several steps forward; at the end of the day, it’s a fascinating game with wonderful “level design” on both macro (branching stage layouts) and micro (each terrifyingly formidable grunt enemy requires a psychologically taxing, back-stepping, ducking, jump-tweaking boxing match unparalleled in action gaming since) levels. Its sequel, the 800-pound gorilla non-Japanese passport-holders call Castlevania: Symphony of the Night, was a bloated, overcooked game with some drop-dead awesome game design ideas, “RPG elements”, and lots and lots of dead air. In it, you play as waify gorgeousman Alucard, who moves like the weightless wind, meaning that the controls were a huge step “forward”, toward adjectives like “smooth” and “pick-up-and-play”.

Between Rondo and Symphony, and well before Symphony‘s ensuing deification and redefinition of what people talk about when they talk about Castlevania, yet another team at Konami had an idea to take the basics of Castlevania — the soul, the friction — and reboot it in a machine-gun paced, no-nonsense, straightforward walk-and-destroy.

The year was 1994, and the console was the Sega MegaDrive. The game was called “Vampire Killer”. In America, we’d call it “Castlevania: Bloodlines”. In Europe, where use of words like “Blood” or “Ninja” were banned wholesale from game titles, they’d call it “Castlevania: Vampire’s Kiss”, which sounds kind of gay. (Like, in a literary sense.) Why was “vampire” okay for a game title, and “ninja” not? They have some hecked-up hangups over there.

I like to think of the lead designers of the three Castlevania reboots (Super, Rondo, and Bloodlines) as three young men, let’s say sons of the King of Konami. They worked together on the first Castlevania games for the Famicom, and chose different sides when the console war — MegaDrive versus Super Famicom versus PC-Engine — began. The lead designer of Super Castlevania IV was the loyal son, always blindly looking to impress Father. The designer of Rondo was the scholar, the go-getter, the strategist, seeking to prove himself superior to all humans, not just to his brothers. The designer of Bloodlines was the slacker, the one everyone assumes could get ahead in the world if he’d just stop hanging out at the tavern with the local band of hooligans. (He can otherwise rip out a hell of a guitar solo. I imagine he also looked like Johnny Depp in that one movie where he first had a beard.)

(A pause to thank Japanese game corporations for locking the details of game development in Top Secret Files: the above is impervious to fact-checking.)

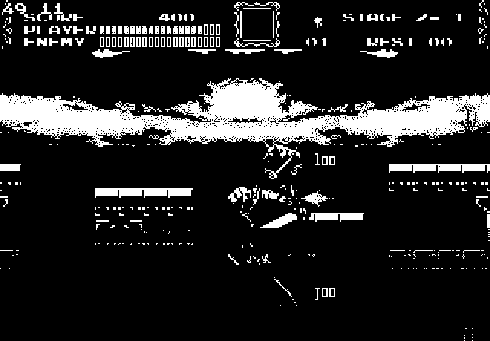

So here’s Bloodlines. You choose between John Morris (guy with whip) or Eric LeCarde (guy with spear). The whip lashes deliciously. The spear thrusts in a most manly fashion, chunking forward and crushing sternums. It’s the best spear physics ever in a videogame. The jumps are weighty, with tweaking only allowed on the way up. On the way down, you drop like a stone. This is crucial. You can swing with the whip.

The game was made by men not afraid to use graph paper or break pencils. Why it was made, we don’t know. We don’t care. The stage-to-stage planning meetings for this game must have involved a lot of conversations that would make small animals’ brains implode. The genre and format of their game was so archetypically established that the game design team (credited as “Bunmin” and “Mamuun”, one of whom may (or may not) be who Wikipedia called “Haruki Yutaka”) didn’t even need to speak in real words like “werewolf” or “skeleton on motorcycle”. They talked about projectiles, numbers of projectiles, angles of projectiles, and enemy characters’ preclusions to step forward and backward (or not do so).

Some of the stages are weirdly conceptual, though it’s never anything as simple as “Fire level” or “Ice level”. There’s one sequence where you play upside down. There’s another (in the same level) where the screen divides up into several little windows, like you’re playing the game on a TV reflected in a broken mirror. For what reason, no one knows. It was presumably just something these genuis slackers wanted to try.

Some of the stages are painfully ordinary on paper, like the Tower of Pisa stage, where you run up unexplained floating bone-like platforms in circles around a cleverly rotating Tower of Pisa. Big enemy gargoyle bastards fly in at you. Time your jumps and master your physics to keep killing, and keep jumping. Painfully ordinary — and violently awesome.

The boss fights are spectacular, hard, fast, brutal, ruthless. They’re proto-post-fighting game matches. Contextually, they make no sense; they are dead men: they tell no tales. They’re precious.

Reading the Wikipedia page for this game is hilarious and amazing. I would like to call special attention to the “Textual References” section. It contains such delicious passages as this:

“* According to the North American manual, John Morris (and his friend Eric Lecarde) were supposed to have witnessed his father’s death moments after he had stabbed Dracula. At the time, John Morris was only two years of age, since he was born in 1895. Also, John and Eric were not mentioned in the novel. The original Japanese and European instruction manuals makes no mention of John and Eric being witness to his father’s death. The novel describes the travelers who chase Dracula, but there is never a mention to any kids traveling with them. Nothing in the game contradicts the possibility of John witnessing his father’s death, regardless of whether his age at the time prevented him from remembering the event.

“* The manual claims Quincy stabbed Dracula with a wooden stake. However, in the novel Quincy uses a Bowie Knife. Additionally, the manual claims it was Quincy Morris that killed [D]racula with no mention of the combined efforts of other characters in the novel. However, in the novel Dracula is killed when Jonathan Harker sliced through Dracula’s throat (implying beheading), while Quincy simultaneously stabbed him through the heart.”

“* Additionally, the Countess Bartley is loosely based on the actual historical figure Erzsébet Báthory. The witch who resurrects her in the game’s backstory is Dorottya Szentes, who in reality had connections to Báthory. (Just as the name “Bartley” in the English versions of the game is a mistransliteration of Báthory, the name “Drolta Tzuentes” is a corruption of Dorottya’s name.)

* The game’s backstory also references the real-life death of Archduke Franz Ferdinand of Austria, suggesting that the assassination had been ordered by the Countess.”

We here at Action Button Dot Net would like to kindly inform you that this kind of instruction-manual-confined “story” — loved and catalogued and loved and worshipped by fans — is almost always invariably the work of one of the design team’s Junior Crew; it must have sucked to be the chubby-fingered girl they hired to research something that looks reasonable for Bloodlines: there was no Wikipedia back in 1994. Hell, there wasn’t even an internet. She probably had to go to the library!

I make this distinction because Castlevania Bloodlines is a sub-B-movie videogame full of disjointed setpieces — you’re climbing up platforms, whipping gargoyles, giant tower miles in the distance one second, and then you jump off the right side of the screen and there you are an instant later, on top of the distant tower, whipping a giant flying boss monster. When you kill the final boss, landing that triumphant, cracking whip-lash, the message

FINAL STAGE CLEARED

flashes up on the screen in giant font, as the typical end-of-stage jingle gleefully chugs out of your (ideally) single television speaker. In a flash, the character of your choice is standing far outside the castle as it crumbles to the ground, and the only in-game story-acknowledging text messages materializes on screen:

THE RESURRECTION OF DRACULA HAS BEEN AVERTED.

Oh, so that‘s what this was all about. I’d been wondering for a while there.

The credits go on to reveal that the bosses have names like “Meat Golem Gear Steamer”, and lists development team members by single-name pseudo-pseudonyms like “Tat”, “Norio”, and “Takemoto” (credited as “Special Design”). I’m pretty sure this is a game that was never planned to be treated like literature; that the lords of Konami agreed to let it be made is a near-direct indication that they don’t consider any member of the series worthy of being considered literature. Bloodlines is all about chug and pump, snap and crunch; it’s a group of grown men with refined tastes entertaining themselves, being sloppy, and having a huge laugh about little things like how the cracked stone staircase to Dracula’s chamber actually manages to cross over the top of the giant full moon.

Years later would see this kind of game design deified by a select group of unwashed yet righteous individuals. The spirt of “Konami on MegaDrive” — exhibited perhaps most purely (and therefore nearly undigestibly) in Contra: The Hard Corps, cutely in Rocket Knight Adventures, and avant-garde-like in Neo Contra (for PlayStation 2) — manages to live on today in games like Capcom’s God Hand. In Neo Contra, with an opening cut scene that shows one of the two heroes literally sitting on top of a jet liner and cutting an oncoming intercontinental ballistic missile in half with his sword, the Konami Spirit is a little too obvious. In Capcom’s God Hand for the PlayStation 2, the humor is a little impenetrable to anyone who doesn’t have at least one conversation on the insignificance of Golden Axe every eight months. In Bloodlines, the “humor” is so subtle and refined it might not even be there at all. There’s a glory in touching it via the game’s play mechanics, tweaking around with it, delving in its distinctly MegaDrivey (Michiru Yamane, in her first soundtrack, made that noisy sound chip breathe), distinctly Konamilike looseness. We would be lying if we didn’t say anything about us being hopelessly in love with weird little disconnects in games — like, oh, say, Ranger X and Thunder Force IV and Monster World IV, all for MegaDrive — with design as subtly ebbing, flowing, and nuanced as a mellow noise-rock record. We’d make a whole list of such games, and we’d spill out tens of thousands of words on their quirks, the not-quite-right angles of the projectiles, the strict hit radii of the player’s standard attacks, and the potato-sack weights of their jumps, though we’d probably end up making some metaphors that would put us under investigation by the FBI. (Game reviewing is dangerous business.) So for our list of the best twenty-five games of all time, if we have to make one selfish, puzzling choice — and our consciences require thus — it has to be Bloodlines. Years later, it still speaks volumes to us, whether or not we will ever have any clue what it’s actually saying.

Years later would see this kind of game design deified by a select group of unwashed yet righteous individuals. The spirt of “Konami on MegaDrive” — exhibited perhaps most purely (and therefore nearly undigestibly) in Contra: The Hard Corps, cutely in Rocket Knight Adventures, and avant-garde-like in Neo Contra (for PlayStation 2) — manages to live on today in games like Capcom’s God Hand. In Neo Contra, with an opening cut scene that shows one of the two heroes literally sitting on top of a jet liner and cutting an oncoming intercontinental ballistic missile in half with his sword, the Konami Spirit is a little too obvious. In Capcom’s God Hand for the PlayStation 2, the humor is a little impenetrable to anyone who doesn’t have at least one conversation on the insignificance of Golden Axe every eight months. In Bloodlines, the “humor” is so subtle and refined it might not even be there at all. There’s a glory in touching it via the game’s play mechanics, tweaking around with it, delving in its distinctly MegaDrivey (Michiru Yamane, in her first soundtrack, made that noisy sound chip breathe), distinctly Konamilike looseness. We would be lying if we didn’t say anything about us being hopelessly in love with weird little disconnects in games — like, oh, say, Ranger X and Thunder Force IV and Monster World IV, all for MegaDrive — with design as subtly ebbing, flowing, and nuanced as a mellow noise-rock record. We’d make a whole list of such games, and we’d spill out tens of thousands of words on their quirks, the not-quite-right angles of the projectiles, the strict hit radii of the player’s standard attacks, and the potato-sack weights of their jumps, though we’d probably end up making some metaphors that would put us under investigation by the FBI. (Game reviewing is dangerous business.) So for our list of the best twenty-five games of all time, if we have to make one selfish, puzzling choice — and our consciences require thus — it has to be Bloodlines. Years later, it still speaks volumes to us, whether or not we will ever have any clue what it’s actually saying.

–tim rogers

Pingback: Ganalot! » Blog Archive » Castlevania Music: BLOODY TEARS COLLECTION

Pingback: Ganalot! » Blog Archive » Castlevania Music: VAMPIRE KILLER COLLECTION

Pingback: The List: Castlevania Symphony of the Night (Part 2) - Theology Gaming