a review of Breath of Fire V: Dragon Quarter

a review of Breath of Fire V: Dragon Quarter

a videogame developed by capcom

and published by capcom

for the sony playstation 2 computer entertainment system

text by tim rogers

Human’s qualified masterpiece Septentrion, barely-known in the west as S.O.S., is easily one of the most elegantly-conceived games of all-time. You play the role of one identically-controlled passenger (of four selectable) on a ship that is sinking in the middle of the ocean in the early 20th century. You have precisely one real-time hour to escape the ship. Along the way, you might come across other passengers who can be rescued. Sometimes the passengers might be people you know, and sometimes they might be people you love. Sometimes, there will be conflicts — like the captain, who refuses to leave the cabin — unless. Every fifteen minutes, the ship rotates ninety degrees, changing the configuration of platforms and/or drowning other survivors. Each player character can rescue up to seven other passengers; which passengers are rescued results in a different ending (there are literally hundreds). The most depressing endings are when a passenger escapes alone, and sits on the belly of the capsized ship, looking at the stars, wondering why no one else made it out alive. The only player actions in Septentrion are walking, running, jumping, and climbing. We would love this game above all other games ever made — and we reckon the entire world would know it existed — if its controls had only, say, a Super Mario Bros. level of polish. They do not. At best, the physics of Septentrion recall the player’s joyous memory of the first time they ever moved a mouse cursor. This unfortunate event sees Septentrion fall just short of “Legend” status, and instead settle for “Archetype”.

Ever since Septentrion, a small and scattered band of light-shunning Japanese social deviants have taken it upon themselves to become millionaires by tweaking the concept of a “survival”-based videogame with a simple central goal of “get the hell out of here”. If you ever meet Shinji Mikami, ask him about Septentrion; he’ll stop chewing his banana and tell you that yes, of course it was an inspiration on Resident Evil. That game was a perfect case of “right place, right time” — coming so soon after its inspirations, though so distinctly different as to look like a brand-new experience. In both games, you’re trying to flee from an undesirable place, though in Resident Evil, the place is full of zombies, and you have a gun. Resident Evil is and was a masterpiece because of its portrayal of logistics — the fear in the game, eventually, comes less from the sneaking suspicion that a zombie dog is going to come flying through that peculiar window and more from the feeling that you only have one bullet left, and you don’t know where to find more. Eventually, because you can shoot the zombies, the times when you don’t are the scariest. Hence Resident Evil‘s chief contribution to the game design gene pool: an eternally clever reversal of the situation wherein guy-on-sofa screams at VHS image: “Don’t just stand there — shoot the hecking guy already!” Resident Evil, alas, ultimately fails to earn the title of “immortal world-class entertainment” because the secret police agents that exist in its world control more like tanks than human beings. The sensation of slowly rotating 180 degrees so as to point a shotgun at an approaching zombie-creep’s face is perhaps as synonymous with the “terror” of Resident Evil as the aforementioned through-window-crashing zombie dog. The pattern, then, is already visible: these polished gamespikes we will call Septentrionlikes are victims of the “pitchers can’t hit homeruns” syndrome. With great focus comes less of a possibility of any action-based gameplay working out perfectly.

The best Zelda game of all-time — and heck you quite politely if you disagree — is Majora’s Mask, also a Septentrion-like; it unfolds over three pseudo-real-time days, and lets the player reset time (and all accomplishments up to that point) whenever he feels the need. Like Dead Rising after it, Majora’s Mask would reward the player for carefully remembering the most clockwork-like behaviors of its world’s every resident. At the end of the day, you had an excellent Zelda game with a handful of actually-interesting dungeons, with this thrilling schedule-management simulation on top of it. Years before Guitar Hero would teach Americans worldwide to love and respect the idea of remembering exactly when to push what buttons within the context of a flowing piece of rock and roll, Majora’s Mask brought us (the open-minded gamers of the world) the joy of a simulated school play.

Dead Rising, perhaps the most popular (and least serious) Septentrion-like, upped the ante by letting us star in a B-movie. Dead Rising, which is as much a secretary simulation as it is a Metal Gear Solid-like with zombie-hacking in place of stealth espionage, teaches the player both to use anything and everything as a weapon and to plan every little event far in advance. The story (if you can call it that) unfolds over the course of three pseudo-real-time days (as in Majora’s Mask) in which a photojournalist bounces between hot spots in a middle-American shopping mall rescuing people from zombies accidentally as he tries to search for clues to unlock the mystery of why exactly all these zombies ended up in a middle-American shopping mall. The protagonist has covered wars before, and is convinced that the story of zombies in a shopping mall will earn him a Pulitzer. The game ultimately fails the Action Button Dot Net Manifesto Criteria Test because it lets the player dress his character up in children’s clothing, and one of the bosses is a clown. Real shame about that clown: we just can’t get behind a game that acknowledges the existence of such a satan-worshipping profession.

Our personal favorite Septentrion-like, if we had to pick just one, would be Irem’s heartbreakingly excellent Zettai Zetsumei Toshi 2 (****), released in the west as Raw Danger. It’s about a partially underwater new-age metropolitan city center that begins to flood during a torrential rainstorm during a Christmas party attended by politicians and other social high-profile types. You initially play the game as a young waiter. There’s a girl you like. The flood quickly evolves from carpet-wetting to concrete-cracking, though not before allowing the player to stew in some amazing environmental juices: the bustling sound of a kitchen, the satisfying friction of pushing a hand cart into the ballroom, the seamlessly hidden tutorial segments (like when you help a woman search for a contact lens), the elevator-music rendition of “Jingle Bells” playing in the hotel lobby. There are some absolute virtuoso pieces of programming on display, such as the way a cardboard box in the hallway falls over precisely when you look at it, the third time you exit the ballroom on your way back to the kitchen. On paper, it’s hard to believe the game was made by just thirteen people; in motion, it’s not hard to believe at all. It clips and chugs as the plot starts to get apocalyptic; it apocalypses whenever there’s anything resembling an action sequence. We can’t recommend it to everyone because of the chunky interface and the admittedly confusing nature of some of the puzzles, though if you’re patient enough to have ever, say, learned a foreign language without expecting school credit, it might end up being your favorite game of all-time.

We’d really like to include Raw Danger in this spot on our list; our hands are held back because of technical problems, all that chunk, some of the meandering, and all that cheese in the story. Granted, the story is supposed to have the light-hearted tone of a Japanese C-grade date movie. (Japanese girls like to see people in love drown, die, or go blind (preferably all three simultaneously), which makes their real-life situation (boyfriend whose “job” leaves him free to only meet once a month) look pretty tame in comparison.) However, it kind of fails in spite of itself for being just a tiny bit too straight at points. It could have been gorgeous if it had gotten a little weird. Or we could just be saying this because we don’t want to give it too strong a recommendation, because then we wouldn’t be the only people who like it so much.

No, if we have to pick one game to represent the not-yet-perfected Septentrion “genre”, it would be Breath of Fire V: Dragon Quarter.

ACTUALLY TALKING ABOUT THE GAME NOW

We’re not sure if this says more about videogames, videogame designers, us, or the world, though we’re pretty sure that the best spin on the “timely escape from an undesirable place” videogame format is not an action game about zombies or a survival game about lovers — it’s a role-playing game with the tone of a German silent film in which “existential dread” and “wide-eyed at-camera-staring” are more than just the main characters: they’re the stars.

Breath of Fire V: Dragon Quarter, is, as the title indicates, the fifth game in a series called “Breath of Fire“, which names an ability frequently possessed by dragons. Previous games in the series had required players to change their lead character (by pressing the L button) on the world map so they could walk through forests, which was both slightly more and much less clever than it sounds. We’re not particularly interested in talking about Breath of Fire as a series, to be honest. Suffice it to say that it gets Big Points on this bingo night we call Action Button Dot Net, for sticking to its guns and starring the same lead character in every installment. Though he always finds himself in different situations, worlds, and bodies, the character is always a young man named Ryu, who never speaks, always ends up meeting a girl named Nina and having his life changed for the more hectic, and without fail eventually discovers his hidden talent for turning into a dragon. Though we have fond memories of actually playing all the way through the first four games — hey, they’re RPGs, and they’re by Capcom (to be honest we only played the first one because EGM revealed that there was a Chun-Li cameo; this was 1993: after that, we were trapped) — none of them invoked the post-final-boss reverent self-flagellation of, say, a Dragon Quest. (In hindsight, we realize that Breath of Fire‘s core concept at the outset of the development might have been to make an RPG for the loads of people who were disappointed that Dragon Quest had been going for seven years and only ever shown the public two genuine dragons.)

Dragon Quarter is mostly brilliant because it’s a “reboot” of the series, and one humbly intended (?) to end the series, rather than start its cash-machine pumping anew. It takes all of the hallmarks of the series (boy named Ryu, girl named Nina, peculiar guy named Bosch, Ryu’s mysterious ability to turn into a dragon), and develops them into a whole new mythos. That some people were actually disappointed with the game says as much about people as the fact that some people complained that Bruce Wayne learned his acrobatic techniques by shacking up with ninjas in “Batman Begins” instead of joining the circus like he did in the comic books. However exasperated we may be whenever some NASCAR fan links us to “Real Ultimate Power” and giggles about the awesomeness of ninjas, we are inclined to agree that Ninjas are indeed infinitely cooler than circus clowns and trapeze fairies.

Of course, rebooting has been the basic thrust of the series from the second installment. It’s always clear that, each time, Ryu is someone new. It’s always clear that the first time he meets Nina in the story is the first time they’ve ever met. It’s irresistibly cute, in a world where other RPG series will keep the same title though wipe the story slate clean, tying their worlds together only tenuously, with the existence of a certain minor character and a race of large ridable yellow birds that were stolen from Hayao Miyazaki in the first place. (Also, the names of the magic spells are the same throughout Final Fantasies, though seriously, when you can point a finger-cursor at one-third of your game’s concept of “continuity”, you might have a problem that it would take an entire library to describe. (Not that there’s anything wrong with that. (Some of the time.))) Most endearingly, Breath of Fire games do connect to one another in a laid-back sort of way: at the end of III, we see our protagonists cross a hideously vast desert, and emerge in the ruins of an ancient civilization. In IV, we see a civilization in the desert and witness a second-degree apocalypse.

Then, in Breath of Fire V, humanity has been living in deep, brown, underground tunnels for perhaps several millenia. The greatest joy perhaps feelable by a human in these psychotic circumstances might be to gaze upon the sky-blue-painted ceiling of one of the more spacious “city” caverns. The Ryu this time around is a young man who works as a kind of police officer in one of the absolutely lowest, filthiest sections of the city. His partner is a young man named Bosch. They are given a mission which turns out to involve locating a young girl. They find the young girl — Nina, a hopelessly white, shiny, frail lab-experimented little waif with no voice and translucent fairy-wings — and Bosch reveals that they must kill her. Ryu reacts with conscience, and manages to ditch Bosch. He eventually has a run-in with a bounty-hunter named Lin, who is trying to rescue Nina. Following an initial misunderstanding (she thinks Ryu is an assassin), they join forces, with one simple goal: escape the depths of this human hell, find the earth’s surface, and see whether or not the prevailing rumor that humans can’t breathe up there is just a myth.

Along the way, Ryu has a spiritual encounter precisely once with a dragon. The dragon awakens in him the ability to transform temporarily into a lizardman-like superbeing capable of breathing laser-fire at an enemy. As the initial spiritual encounter with the dead dragon ghost is very careful to foreshadow, use of this dragon ability drains Ryu slowly of his human soul. This is play mechanic and thematic element rolled into one: the longer you hold down the laser-fire button, the more Amazing Damage you score on an enemy; all the while, a little meter at the top of the screen rolls toward 100%. If that meter reaches 100%, Ryu is dragged into the depths of rampaging perma-dragon psychosis. With graphic design reminiscent of invigorating communist propaganda, the screen goes red, as a black spiky silhouette freaks out. This is a Game Over the likes of which Hideo Kojima can only dream: you are allowed no continue. You must start the game over from the beginning (with all your stats, levels, and stored items intact).

This mechanic really pulled a number on the peanut-butter-and-jelly-subsisting manboys of the world, those semi-men for whom being trapped in a Target store after closing is a fear realer than death. Fun fact: some gamers hate to play a game with a time limit. They will refuse to play a game that limits the amount of time they have to complete any given challenge. Upon injecting their Xboxen with Soul Calibur IV, they will likely access the options menu with a quivering immediacy, and their hearts will not cease fluttering until the match timer has been set to “infinity”. Funnily enough, Dragon Quarter‘s “time limit” has an even more amazing psychological effect on gamepeople, in that it only approaches its limit in direct response to your actions. This, too, owes something to Septentrion: in that game, you are only shown the amount of time remaining before the boat fully sinks when you “die” — by falling from a significant height. After falling, you lose consciousness for five minutes, which is represented by a one-second black-screen flash and then a title card representing the precious number of minutes remaining. Though Septentrion‘s use of a timer is indeed shockingly brilliant, in Dragon Quarter, the psychology might be a little bit stronger: that meter is always there on the screen, whether you’re fighting a battle or not. It’s remarkable; it’s amazing. It’s always there, staring you in the face.

Here we regret to inform you that the game actually gives you too much dragon power. It would be excellent — for, well, reformed kleptomaniacs like ourselves — if the game provided you with just enough dragon power, though that’s a tricky thing to balance in a game that plays out over the course of around a dozen hours. (Either way, too much dragon power or not, even if you don’t ever use it all, it’ll still creep the hell out of you as you play, especially if you give up without reaching the surface.) There’s a reason Septentrion is so deliciously balanced, nipped, and tucked with regard to scenario flow and level design: it’s because the game is never meant to take longer than one hour to clear.

Dragon Quarter can be cleared in less than ten hours, if you be the owner of common sense. To quote IGN.com‘s review:

“Sadly, there are quite a few negatives . . . [t]he most prominent of which is what we discussed at the beginning of our essay: the overall length of the game. Now[,] if you’re good, you can beat this sucker in under 10 hours your first time through (counting cut scenes), and perhaps even quicker with each subsequent trip since you can keep equipment, skills, and other such bonuses from earlier spelunking. It’s a double-edged sword really: as it’s great to be able to continue to rise in rank and discover new things every time you play, [just] not so cool that each time through is so terribly short.”

IGN considers the “brevity” of Dragon Quarter the game’s “most prominent” “negative” because . . . why? Why, because the game plays somewhat like a role-playing game made by Japanese people, and those games tend to be longer than forty or fifty hours. They admit a paragraph previous that one of the “prominent” “positives” is that you can and will want to play through it multiple times. The conclusion of this segment of our review is that IGN considers their reviews “essays”, that Some People Don’t Get Stuff, and that We Don’t Really Like spending more than a dozen hours doing anything, even being sexually tortured by our Supermodel Mistresses.

IGN goes on in their review to say “Breath of Fire: Dragon Quarter is certainly one of the better looking RPGs on Sony’s system, and with Final Fantasy X and Dark Cloud 2 excused, it could be the most impressive overall.” We’re going to stop picking on IGN right now, immediately after pointing out that, yes, Breath of Fire V: Dragon Quarter is indeed an RPG, and that most people who don’t like it or even consider it awesome are perhaps most directly influenced by the fact that the play mechanics in the game rely in part on numbers and menus.

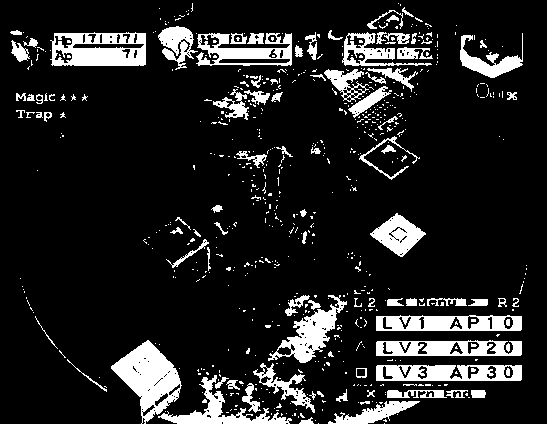

This is certainly true, though it’s nothing to beat yourself up over: Dragon Quarter, in addition to being a short RPG, is also a relentlessly elegant one. Battles are not random — they are initiated by contacting enemies in the field, and when the battles begin, the action takes place on the precise section of field where the enemies and players stood prior to the battle beginning. Other RPGs had experimented with battles taking place using the actual field map as the background (Breath of Fire IV), many had experimented with battles being initiated by touching enemy representatives on the field map (Lufia II and Mother). However, even those RPGs who tried both of these radical elements at once didn’t quite “get” it: Chrono Trigger‘s battles start when the player makes contact with enemies on the field map, and the fights occur on top of the actual field map itself; however, the enemy encounters are, more often than not, unavoidable, and the positioning of the characters on any respective battlefield is hardly ever more than just a graphical effect. Dragon Quarter‘s battles require the player to move his characters around tactfully and tactically, implementing elements of roguelikes and tactical strategy RPGs into one weirdly seamless experience. In this vaguely steampunked world, the gliding in of menus and expansion of wireframe hit bubbles cannot possibly shatter the mood: neon green looks great against stuff brown.

It helps that the battles for Dragon Quarter are so supremely well-thought-out, and that their seamlessness runs deeper than just the transitions from the field map. In a sense, the entire game is one continuous struggle, one flowing battle-like experience. Just, sometimes, you can’t see any monsters. And when you can see the monsters, and they can see you, yYou’ll be setting traps, bottlenecking, choke-pointing, flanking, and suppressing your enemies, and even taking cover behind boxes or obstacles so as to keep your enemy from gaining immediate access to you, buying precious time.

Dragon Quarter‘s battle system would later be lifted up and transplanted into Sega’s Valkyria Chronicles for the PlayStation 3, which applies the mechanics to a much larger scale — battlefields involve dozens of soldiers, and unfold over entire cities with rooftops and sniper towers. As excellent as Valkyria is (it’s virtuoso entertainment for any RPG-lover, actually: like Dragon Quarter, it combines towns, dungeons, field questing, and excellent battles into one flow), it’s hard to beat the in-your-face intimacy of Dragon Quarter, in which you will only ever have three characters, each with a very limited and very different ability set, each of them absolutely vital to truly master any given battle. At its highest points, it’s neither an “RPG” nor a “strategy game”: it’s just a videogame, and it’s moving forward with or without your preconceptions.

There is a Metal Gear Solid 3 boss-fight level of virtuosity behind even the most mundane random encounters in Dragon Quarter, wherein you will know you are clever when you win. If it’s an RPG, it doesn’t require any grinding: you can play it straight through. It’s like Vandal Hearts, in that way: an RPG you can play like an old-school action-shooting game, delicately applying brainpower in all the right places to literally slide right through. (Vandal Hearts gets bonus points, because it might actually be possible to complete every battle without a single one of your characters being hit once. We haven’t tested this, though, because doing so would require us to probably stop touching ourselves for several weeks: supreme strategy requires numbing celibacy.) Here we can compare Dragon Quarter to MegaMan: though certain weapons and tactics are ideal for defeating certain bosses, a player with high adaptability can theoretically play through the game using only Massive Wits and The Action Button. This is excellent. Each battle is frictive with moments ike in Vandal Hearts, where you position a soldier behind an enemy and come in with a back-stabbing instant kill, only in Dragon Quarter, the thrill is more abstract, transient, beautiful, snowflake-like: close one eye, lean in the right precise direction, extend the arm, snap the spear, skewer everyone at once.

Alternate way of praising Dragon Quarter‘s battle system: the bosses tend to be just people the same size as your party members. We love stuff like that.

If you die in Dragon Quarter, you can choose to restart the entire game with all of your experience and stored items intact. This allows the player to “rehearse” the game; the exact same game design team would later use this tactic in Dead Rising. It’s our opinion that maybe the first sign that your Septentrion-inspired game isn’t quite as well-designed concept-wise as Septentrion is that the “rehearsal” element involves anything resembling experience points. Yes, we know that people love “numbers and stuff”, and that some people refuse to play a game without numbers, though really, would “Terminator 2” be a better film if a running tally of “shots fired” streamed along, omni-visible, at the bottom of the screen? We’re being contrary here, for sure, and — nah, you know what? What the hell — the D-counter at the top of the screen in Dragon Quarter is without a doubt the Most Conceptually Hilariously Awesome Number in videogame history, and its presence allows us to forgive any and all other numerals present in the game. To back this (whatever “this” is) up, let’s go on record and say that the replaying-the-game mode of Dragon Quarter is only really “necessary” if you’re the type of person who equates “RPG” with “choose ‘FIGHT’ every round for every character, never die, clear game forty hours later”. In other words, if you’re a schlub — a doily-fluffer. Quite fittingly, the “Scenario Overlay” (SOL) “system”, in which the game shows you deeper (and unnecessary) details about the story only activates as you re- and re-replay the game. This is quite the nod to experienced players (maybe): if you’re clever enough to play straight through the game, you’re probably also clever enough to read between the story-lines and soak in the game’s meticulously crafted atmosphere for yourself.

Indeed, the truest trumpet blast proclaiming Dragon Quarter‘s greatness is said atmosphere. Insects cling to flickering lights in psycho-depressing underground metal stairwells, words are scarce (what’s to talk about?), elevators are a “mode of transportation”, people in “cities” slump against rock walls, everyone hates everyone else, everyone hates their self, everyone hates everyone else for hating themselves. That the game’s characters and players share the same desire re: getting the hell out of this depressing place is more than just a coincidence: it’s good game design. And it would be perhaps nothing without excellent music: thankfully, demigod composers Yasunori Mitsuda and Hitoshi Sakimoto are on hand to provide one of the best game soundtracks of all-time, bubbling, suppressed yet brassy electro-industrial sound-vapor, full of screaming intensity during battles, pulsing dread for dungeon-creeping, and whimpering ambient hatred for all the poignant parts.

Above all else, Dragon Quarter is a game about presenting the player with a scenario and seeing it through to its conclusion. It is about an exodus from an undesirable place within strict (psychological) time limitations. It doesn’t overstay its welcome, which is a miracle given how fiercely dark and hopeless it is at all times, with the glowing, white, innocent, girlish Nina, ever-present, the only on-screen / “in-game” representation of “hope”. The final boss of this game is another human, one whom the main character meets at the beginning of the game, fights once, and then doesn’t see for several hours until the very end of the game. This is the kind of RPG Fumito Ueda would make, if he didn’t have a well-documented dislike of non-player characters (he says, the first time a player makes an NPC say the same line of dialogue more than once, the game is shattered in his eyes) and stat-numbers. We’re putting Dragon Quarter right here on our list partially to egg Mr. Ueda on: this game points to a future of blockbuster quest-based stories with razor-sharp final goals, simple and malleable mechanics, one strict, tension-inducing visual / game-design element, and a small, close-knit group of main characters. Really, the less characters, the better. Actually, if you’re going to make another game with a tight time limit, give up the desire to represent a day-night cycle (Dead Rising and Majora’s Mask both take place over three days) and be more like Septentrion. If you can, make a game that presents fifteen hectic minutes in a perfectly envisioned world on the brink of disaster, where every death is an “ending”. At sunset. (Or sunrise.)

Above all else, Dragon Quarter is a game about presenting the player with a scenario and seeing it through to its conclusion. It is about an exodus from an undesirable place within strict (psychological) time limitations. It doesn’t overstay its welcome, which is a miracle given how fiercely dark and hopeless it is at all times, with the glowing, white, innocent, girlish Nina, ever-present, the only on-screen / “in-game” representation of “hope”. The final boss of this game is another human, one whom the main character meets at the beginning of the game, fights once, and then doesn’t see for several hours until the very end of the game. This is the kind of RPG Fumito Ueda would make, if he didn’t have a well-documented dislike of non-player characters (he says, the first time a player makes an NPC say the same line of dialogue more than once, the game is shattered in his eyes) and stat-numbers. We’re putting Dragon Quarter right here on our list partially to egg Mr. Ueda on: this game points to a future of blockbuster quest-based stories with razor-sharp final goals, simple and malleable mechanics, one strict, tension-inducing visual / game-design element, and a small, close-knit group of main characters. Really, the less characters, the better. Actually, if you’re going to make another game with a tight time limit, give up the desire to represent a day-night cycle (Dead Rising and Majora’s Mask both take place over three days) and be more like Septentrion. If you can, make a game that presents fifteen hectic minutes in a perfectly envisioned world on the brink of disaster, where every death is an “ending”. At sunset. (Or sunrise.)

Final Fun Fact: Breath of Fire V: Dragon Quarter‘s opening monologue — the only spoken part of the game — is delivered in the Japanese / English / German pseudo-hybrid mock-language developed for Panzer Dragoon Zwei. It may or may not delight any amateur linguists in the audience to know that we here at Action Button Dot Net have quite coincidentally included two other games that use this same mock-language in our list of the best twenty-five games of all time. This is purely an accident; however, if you’d like, we can pretend it’s not.

–tim rogers

Pingback: The Legend of Zelda: Majora’s Mask | Waiting for Miyamoto